Anne Richard, IRC’s vice president of government relations and advocacy, reports on her recent trip to Liberia in today’s edition of The Globalist.

On a visit to Liberia in December 2004, I came away asking, “Who will step forward to lead this country?”

I met with a variety of officials — from teachers and health clinic workers in remote Nimba County to the Minister of Planning and senior UN advisers in Monrovia — to discuss the prospects for lasting peace in Liberia after 14 years of conflict and war.

Adult soldiers turned in weapons so they could return to — what? Without jobs, without health care or prospects, they are a disaster waiting to happen, a mob waiting to riot.

The memory of a conversation with one Liberian colleague lingers — Franklin King is a water and sanitation engineer with the International Rescue Committee (IRC).

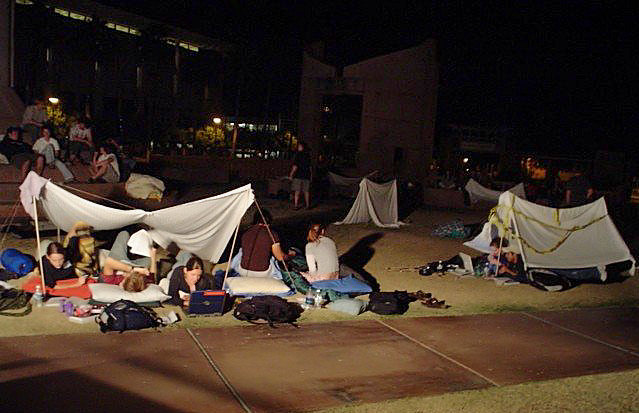

Touring a crowded displaced persons camp outside Monrovia, he pointed out wells and latrines built to help the displaced lead healthier lives.

On the trip back to town, Franklin explained that he was descended from the former American slaves who had settled the country, part of the Americo-Liberian elite that had ruled Liberia since its independence in 1847.

A tragic past

His grandfather had been President and his father was in the House of Representatives during the Tolbert government. The last time Franklin had seen his father alive was on the beach in Monrovia in 1980. The families of 13 ousted government officials were brought there to watch the executions of these men.

Franklin seemed almost apologetic when he explained that he had shunned politics to work as a sanitation engineer.

Franklin’s choice

Franklin’s choice struck me then as a very sane decision, but has worried me since. Few families in Liberia have been untouched by war and displacement.

The number of people in Liberia with the education, energy and optimism to work for positive change and not just whatever they can extort, appears very small.

The number of people with the education, energy and optimism to work for positive change in that country — and not just whatever they can extort or skim off the top — appears very small indeed.

For now, Liberia is run by a “transitional chairman,” businessman Gyude Bryant, and a power-sharing government that includes ex-rebels. Security is maintained by UNMIL (United Nations Mission in Liberia), the UN’s integrated peacekeeping and humanitarian assistance mission.

UNMIL is led by Jacques Klein, the voluble American diplomat who had served as the UN Secretary General’s special representative in Bosnia and Eastern Slavonia before being recruited again for UNMIL.

Engineering a government

Bryant and Klein have their hands full trying to maintain the peace on a shoestring budget, yet they and UNMIL are somehow also expected to engineer a government that can pay salaries to public servants, take actions to curb corruption and manage public funds and agencies in a transparent manner.

In October 2005, an election will be held to choose a new president and parliament, and power will (knock on wood) shift. The field of more than 45 likely candidates for the office of president is crowded and uneven.

Presidential contenders

Leading contenders include Winston Tubman, a former UN envoy to Somalia (and nephew of a former president), Varney Sherman, a legal consultant and advisor to Bryant, and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf — a former World Bank and UN official.

After he had witnessed the execution of his father and other members of parliament, Franklin shunned politics to work as a sanitation engineer.

Perhaps the candidate with the greatest name recognition and public appeal in Liberia is George Weah, a former professional soccer player who left school at an early age.

Ex-President Charles Taylor is not on the scene, but is still very much on the minds of the people with whom I met.

While many Liberians are grateful that U.S. President George W. Bush’s involvement helped remove Taylor from power in August 2003, there is much suspicion that Taylor still has the economic and political reach to influence events in Liberia from his exile in Nigeria.

More than just elections

Meanwhile, about 100,000 ex-combatant men, women and children from several warring factions have been disarmed. Adult soldiers who turned in weapons were given a small cash payout so they could return to — what? Without jobs, without health care, without prospects, they are a disaster waiting to happen, a mob waiting to riot.

In Liberia, the “DD” part — disarmament and demobilization — of the peace operation has been successfully concluded. However, the “RR” — rehabilitation and reintegration into society — has been under-funded and requires urgent attention.

A call for leaders

Where are the caring leaders who will step forward to engage in construction — and not destruction?

In Liberia, the “DD” part — disarmament and demobilization — of the peace operation has been successful. However, the “RR” part — rehabilitation and reintegration into society — requires urgent attention.

They are battered and bruised, but they are there in Liberia or in neighboring countries or among the 400,000 Liberians in the United States and Canada, waiting to see what will emerge from the October 2005 elections.

The United States, the European Union and the United Nations have agreed to help pay for the elections, but more than just elections is needed.

Programs that help to mend societies, put people back to work and keep them healthy also deserve support.

And Liberians need the assurance that the United States and others in the international community will stick with them, follow through on funding commitments and work together to restore peace and stability, democracy and prosperity.

Only then will the local heroes — teachers, nurses, social workers, community activists, village elders, small businesspeople — come forward to lead Liberia.